Exploring our local surroundings can reveal hidden meanings in familiar places. It’s possible to casually pass by a historical landmark or an intriguing site on the way to the shops, or even live in a house that was once owned by a renowned industrialist. By delving into the history of our area, we can feel a sense of connection to the past and gain personal insights about our place within it.

In this article, my goal is to explore the history of Whalley Range by delving into the archives of Manchester Central Library. I hope that this exploration inspires you to embark on your own research on your local area. Who knows what revelations you might uncover just beneath the surface?

Who’s Brooks?

In 1819, the Brooks brothers relocated from Manchester to Blackburn, where their father, William Brooks, operated a bank since 1792 called Cunliffes. Among the three brothers, only Samuel, 27 at the time, was entrusted with responsibility of opening a new branch in Manchester, which he accomplished with great success. He brought with him his wife, and two young children.

It is said that he used to regularly advise his young bank clerks on the importance of thrift and demonstrated it himself by consistently arriving at the bank for 8:30am, having travelled on horseback from Whalley Range. Another anecdote claims that during his club dinners, he would take note of members who displayed excessive indulgence, as they could potentially become overdrawn and unreliable debtors at the bank. He had many friends who sometimes referred to him as “old Stink o’ Brass” or simply “Brass.”

In 1824, an economic boom and excessive printing of paper money led to over-speculation, which resulted in a financial crisis in 1825. The crisis triggered a wave of panic withdrawals from banks, leading many of them to fail. Sources show that Samuel Brooks, an astute individual, responded to this crisis by adding layers of gold coins (freshly heated to appear newly-minted) to the top of sacks of meal sourced from the nearby Shudehill Market. He then displayed these sacks in the bank to reassure customers of the bank’s abundant cash reserves and dissuade them from withdrawing funds. This tactic was successful in saving the bank and bolstering its reputation, leading to further success.

The Rise of the Range

From the 1820s onwards, wealthy merchants and professionals in the town began seeking homes in the country suburbs. The growth of factories, particularly those utilizing textile machinery, had ruined the town centre, leading to the increase of slum-dwellings with little to no sanitation due to the absence of health or building regulations. Consequently, the wealthier families felt compelled to relocate elsewhere.

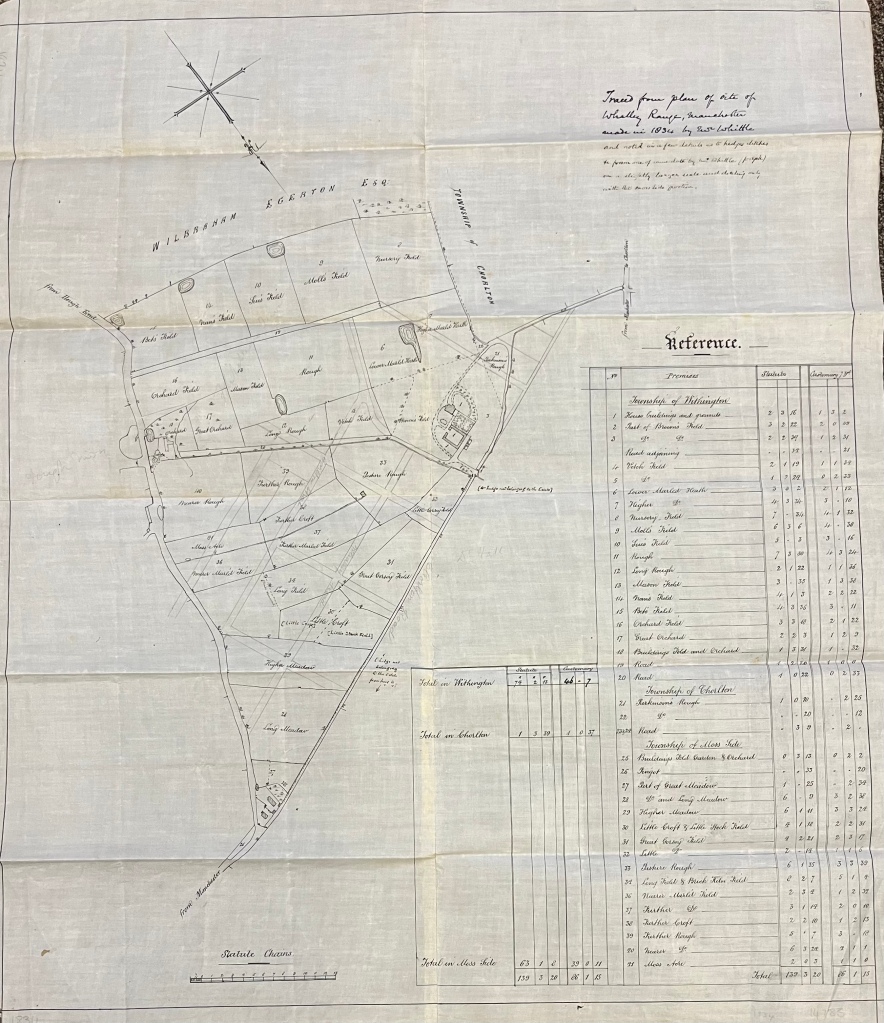

In response, Samuel Brooks wisely began to purchase land a few miles south of Manchester beyond Moss Side, with plans to develop it into an attractive estate similar to those found in London for middle-class gentlemen and their families. The land had previously been utilized for farming purposes, and in 1834, Samuel and his brother John paid £9600 for approximately 63 acres of it.

Samuel’s first estate plan from 1840 featured broad roads with several grand mansions situated throughout the estate. His reputation was as a “great land improver”. He continued to build estates even further outside of town, extending as far as Sale, Timperley, and Carrington Moss.

Samuel Brooks died on June 7, 1864, age 71, at Whalley House, which he had constructed and inhabited since 1833. He died of natural causes. His son, William Cunliffe Brooks, inherited the business and became the sole partner. Samuel Brooks’ remaining estate, valued at £2.5 million, was divided among his two sons and five daughters. As per his specific request, his coffin was transported to Whaley, his birthplace, and buried in a simple grave.

Lancashire Independent College

In 1843, Samuel’s wife Margaret passed away. That same year, he made a significant contribution towards the construction of the Lancashire Independent College, which was relocating from Blackburn and intended for the training of Congregational ministers. The foundation stone for the College was laid on September 23, 1840, but a near tragedy occurred at the ceremony when a stand, hastily erected to seat the ladies, collapsed due to bad weather.

Despite this, the College opened on April 25, 1843, as a beautiful building surrounded by spacious grounds. The preachers trained at the College were invited to hold Sunday evening services in a room above the stables at the Brooks residence when travelling back to Manchester became inconvenient. Although the college is no longer used for training Congregationalists, it still stands today and served as a hall of residence for university students for a time. Currently, the building functions as the Muslim Heritage Centre, both a hostel and a mosque.

Alexandra Park

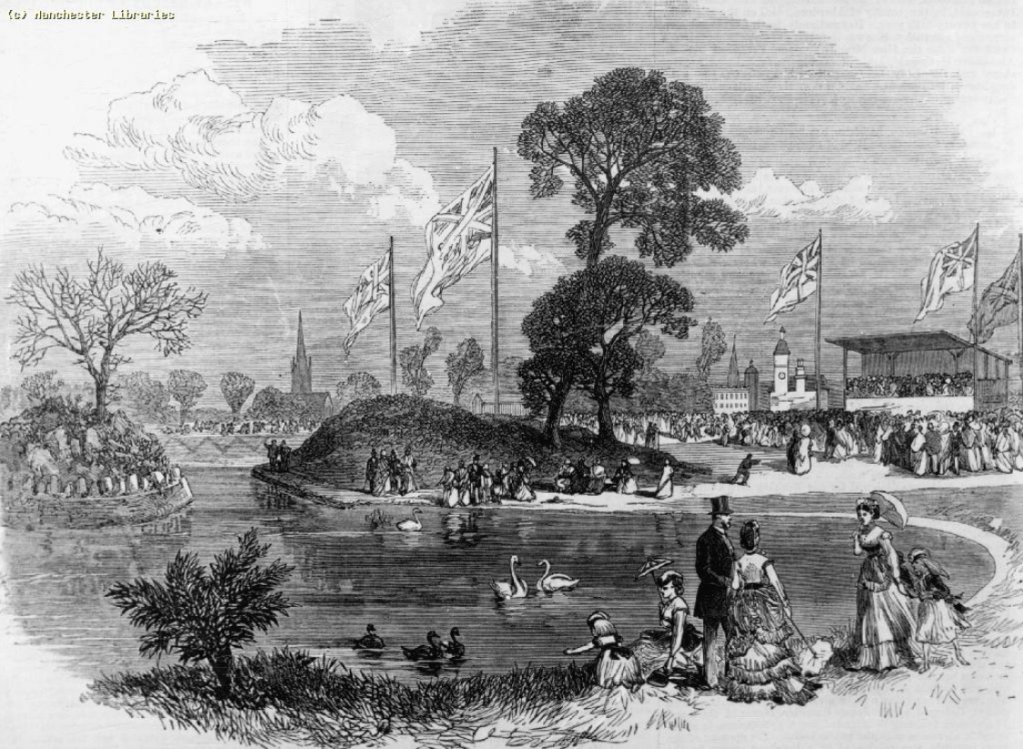

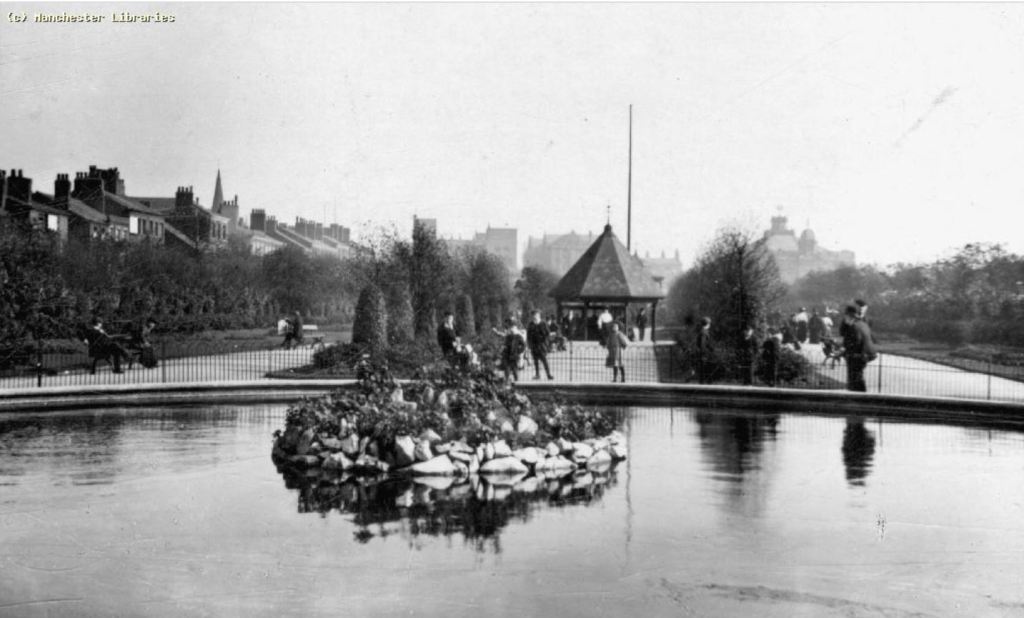

On August 6 1870, Alexandra Park was dedicated after being bought by Manchester City Council from Lord Wilbraham Egerton, for £24,000. It spans 60 acres and was the third park acquired by the Council for public use. During this time, Moss Side was renowned for its picturesque countryside. In that time, strolling through Moss Side, you would see cattle grazing, green cornfields, farms and halls, blooming orchards.

Today, Moss Side presents a striking contrast to its former idyllic countryside, as property speculators and builders rapidly encroached upon the Moss Side district, bringing about a stark transformation. In a short span of time, the once serene countryside gave way to a forbidding urban landscape dominated by imposing red brick structures. The contrast between the past and present serves as a reminder of the changing times and the evolving nature of landscapes and communities.

Alexandra Park used to have numerous attractions that are unfortunately no longer present. To demonstrate the change, I would like to highlight some intriguing features and incidents that occurred in the Park over the years.

Balloon Ascent Tragedy

In 1889, an unusual event occurred at Alexandra Park when Professor Higgins and his assistant Lennox were hired to perform a balloon ascent from Alexandra Park Racecourse on July 16th. Due to strong winds, plans for a parachute landing in the racecourse were abandoned. Nonetheless, the ascent was made to satisfy the crowd, with Lennox ascending in the car attached to the balloon.

Professor Higgins, however, decided to jump from a great height using the only parachute carried for the purpose of exhibition jumping rather than safety. He fell into the pond in Alexandra Park but emerged unhurt. Unfortunately, the balloon suddenly collapsed, and Lennox was dashed to the ground, resulting in his untimely death.

After the tragic incident, Lennox’s body was taken to the old Farmer’s Arms in Burnage Lane. Professor Higgins, also met a tragic end a few years later after an ascent in Leeds.

The Cactus House

One of the Park’s prominent and internationally renowned attractions was the Cactus House. This botanical marvel housed a unique collection of cacti valued at £10,000 and was built between 1905 and 1906. It was visited by botanists from all over the world and was one of the top draws of Manchester’s most popular parks.

On the night of 11 November 1913, an explosion rattled the residents living near Alexandra Park. The following morning, it was discovered that the Cactus House had suffered severe damage amounting to approximately £200. The police suspected that the Suffragettes were responsible as they found two bicycle tracks leading from the fence to the glasshouse, women’s footprints, and the remains of a 3-inch pipe with a time fuse and cap attached near the wreckage at the back entrance. Although there was no direct evidence, this was similar to what the Suffragettes did at Kew Gardens. The majority of the destruction was inflicted on the building’s structure, with minimal harm caused to the plants, though they may have suffered some damage due to exposure to the air.

Manchester Aquarium

The opening of Manchester Aquarium in 1874 on Alexandra Road South marked the city’s first ever aquarium, which also happened to be the largest in the country at that time. With 68 tanks full of exotic sea creatures such as sea anemones, the blobfish, red-spotted blennies and obese dragonfish, it must have been a mind-blowing experience for the Victorians of Manchester who I imagine would have seen them as aliens.

The aquarium housed mechanical tanks that could simulate different tidal waves and ebb and flow. The sea water was brought in barrels by train from Blackpool, 40 miles away, with a constant supply maintained.

Regrettably, the aquarium only lasted for three years, until it was bought in 1877 by Bishop Vaughan to serve as a Catholic schoolhouse, St Bede’s. If you walk into the main hall, you’ll notice a dip in the floor, which is an impression left by weight of the heavy tanks.

An Invitation

In researching my area, the places I walk past everyday, the familiar gained new depth and meaning. I understood that where I live has great historical significance, in fact all areas have hidden historical gems. I invite you to explore your area and discover a new meaning to the places you live. If you are interested in researching the Archives yourself, we invite you to share any information you find about your area.

Links to the collections I used for my research are listed below:

- Manchester Local Image Collection

- British Newspaper Archive (can only be accessed on computers in Manchester Libraries)

- Manchester library catologue

- GMlives – archives database

- Map collection held in Archives+

Sources

- Centenary of Alexandra Park 1870-1970 Souvenir Programme. Manchester: The Trafford Press Ltd.

- Bartle, Julie. (1981) Whalley Range Estate.

- “Bomb in Plant House” (November 12, 1913), The Times (London, England)

- “News in Brief” (July 17, 1889), The Times (London, England)

- “An Aquarium at Manchester” (May 23, 1874). The Times (London, England)

This blog has been written by a student on work placement from We Grow: We Mind the Gap.

What an outstanding piece of work by the student of local history… This person wants congratulating on an excellent piece of forensic homework! Easy to read, fully understandable and congratulations go to all involved… Paul Newsham, ex Levy boy👍

Thanks!

Thank you for your very kid comments – much appreciated!